Slow feed hay nets are very popular for horse owners. They are available to fit all types of bales: from small square bales to large rounds and squares. But how much are they actually helping our horses? In research I conducted at the University of Minnesota with my advisor Dr. Krishona Martinson, we found that using a slow feed or extreme slow feed net significantly increased time to consumption compared to just feeding on the ground or using a “traditional” hay net. On average, horses were able to consume a meal (about 1% of their body weight in hay per meal, fed twice daily) in about 3 hours when fed on the ground or with a traditional net. When we fed the same amount in a medium-sized net (1 ¾” holes), they took about 5.5 hours, and about 6 hours in an extreme-slow feed net (1 ¼” holes). This is extremely helpful for horse owners who are limited to only be able to feed their horses twice daily. It is important for horses to have constant access to forage throughout the day, as horses evolved to consume small amounts consistently through each 24 hour period. Horses only have the ability to produce saliva when chewing, and so if long periods of time are spent not eating, stomach pH can be lowered due to limited introduction of buffers (saliva). There has also been an established relationship between limited time consuming forages and development of stereotypies (cribbing, wood chewing, and stall walking for example). Other benefits of using slow feeders are decreased stress, as our research found that horses that were able to consume for longer periods of time using the slow feed hay nets had lower cortisol levels compared to horses fed on the ground. Researchers also found that waste is significantly decreased when slow feeder nets are used compared to feeding without a net. In one trial, over half of all round bales (55%) was wasted when no feeder was used, compared to only 5% waste with the slow feed round bale net. There are many situations where slow feed hay nets are a great idea to incorporate into your management plan. However, it does not fit all horses. Instances where you may not want to use one is for underweight horses where you are trying to add weight, and some young horses that may be prone to frustration and can develop some negative habits. If using a round bale net, make sure to use another feeder such as a ring feeder, particularly if your horses have shoes or are wearing blankets. This will avoid horses getting caught in the net. If you have any questions as to whether using a net is a good idea for your horses, or how you can implement it into your management plan, don’t hesitate to contact us!

2 Comments

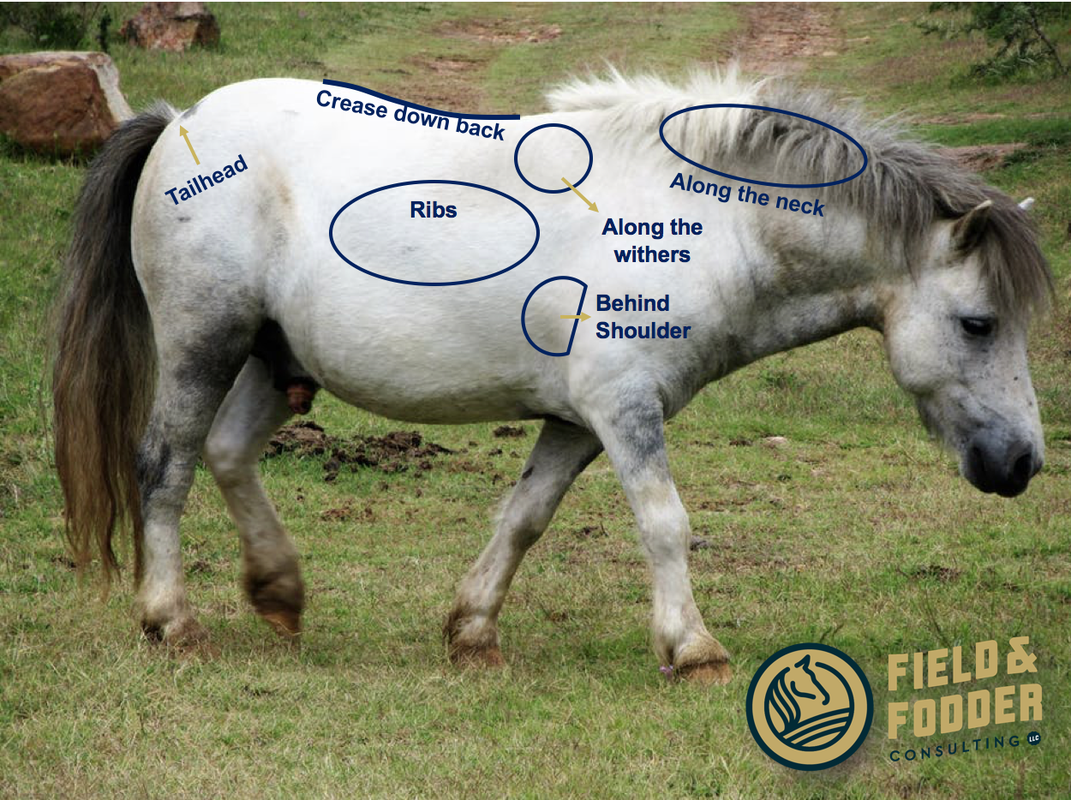

Body condition scoring (BCS) is a valuable skill, which we recommend all horse owners and managers practice often on their equine herds. The system was developed to help one visually assess the amount of fat cover on a horse, which of course is tied to their overall health. Too little fat cover is a sign of unthriftiness, while excess fat cover can lead to other problems- such as metabolic disorders. Monitoring changes in body condition, whether it’s your show mount, a broodmare, or your weekend trail warrior, can help you determine the energy balance of your horse’s diet or give you clues to other lurking issues. Your horse’s BCS is one of the first things we’ll ask or help you determine when evaluating your horse and their diet. The Henneke Horse Body Condition Scoring System is a great tool to use because it utilizes a standard scale, which can then be added to your records and shared with all your equine health care and management professionals. The score can then be tracked for changes over time, rather than trying to rely on memory or a visual weight estimate, which many studies have determined to be unreliable as equine owners consistently over- or underestimate weight by as much as 150-200 pounds. The Henneke system scores fat cover in the following areas: over the ribcage, behind the shoulder, around the withers, along the top of the neck, down the crease of the back, and around the tail head. Evaluating these six fat-accumulating areas of the horse’s body determines where they may lie on the 1 to 9-point scale. The thinnest designation on the scale is a 1, and the fattest is a 9, while a 5 is considered ideal for most equine breeds and body types. Use the descriptive chart below to help you determine your own horse’s BCS. Be sure to both visually inspect the six fat-collecting areas and palpate the thickness with your hands. Some horses may deposit fat unevenly, so try to give each site its own score and then average them together for best results. 1. Poor – Extremely emaciated. Spinous processes, ribs, tailhead, hips, and lower pelvic bones project prominently; bone structure of the withers, shoulders and neck are easily noticed. No fatty tissue can be felt.

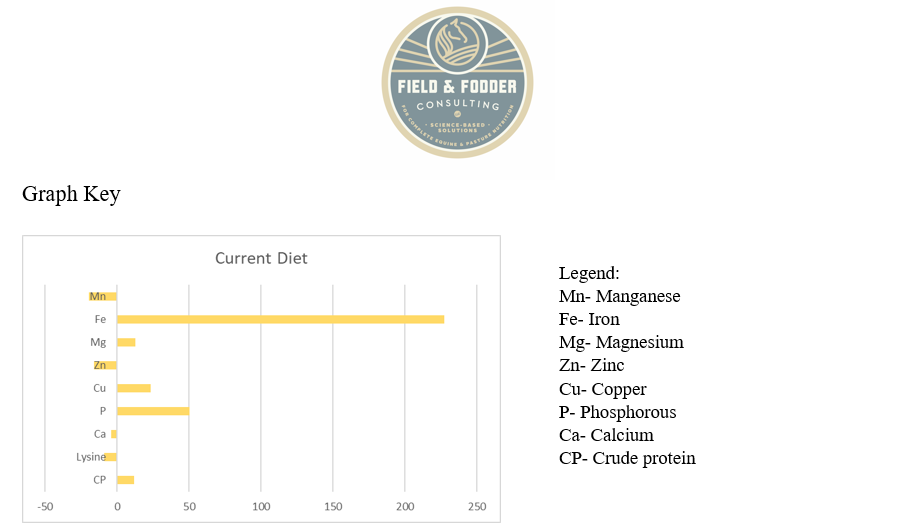

2. Very Thin – Emaciated. Slight fat cover over base of spine; ribs, tailhead, points of hip and buttock prominent; bone structure of the withers, shoulders, and neck faintly discernable. 3. Thin – Fat buildup about halfway on the spine; slight fat cover over the ribs; spine and ribs easily discernable; tailhead prominent, but individual vertebrae cannot be identified visually; points of hip appear rounded but easily discernable; points of buttock not distinguishable; withers, shoulders and neck accentuated. 4. Moderately Thin – Slight ridge along the back; faint outline of ribs discernable; fat can be felt around tailhead, but prominence depends on conformation; Hips not discernable; withers, shoulders, and neck not obviously thin. 5. Moderate – Back is flat with no crease; ribs easily felt, but not visually distinguishable; fat around tailhead feels slightly spongy; withers appear rounded over spine; shoulders and neck blend smoothly into body. 6. Moderately Fleshy – May have slight crease down back; fat over ribs fleshy; fat around tailhead soft; small fat deposits behind shoulders and along the sides of neck and withers. 7. Fleshy – Might have crease down back; individual ribs can be felt, but noticeable filling between ribs with fat; fat around tailhead is soft; fat deposited along withers, behind shoulders and along neck. 8. Fat – Crease down back; difficult to feel ribs; fat around tailhead very soft; area along withers and behind shoulders filled with fat; noticeable thickening of the neck; fat deposited along inner thighs. 9. Extremely Fat- Obvious crease down back. Patchy fat appearing over ribcage; bulging fat around tailhead, along withers, behind shoulder and along neck; fat along inner thighs may rub together; flank filled with fat.  By Emily Meccage, PhD In this four part blog series, we are going to be discussing various methods of restricting or prolonging forage consumption in your horses, as well as how to measure your horse’s body condition. In recent years, the number of overweight and obese horses has increased. Grazing muzzles have been widely promoted in the horse world to allow horses access to pasture and socialization while decreasing caloric consumption. But how well do they work? The first published studies evaluating effectiveness were performed in the UK. These projects found an 80-83% reduction in intake when the muzzles were used. They measured intake by collecting urine and feces and “back-calculating” caloric output and intake. In a study that I conducted with my advisers at University of Minnesota, we measured intake restriction by measuring grass production directly. We also wanted to see if grass morphology, or structure, affected intake with the grazing muzzle. Overall, no matter what grass species was grazed, effectiveness appeared to be similar.  Overall, we are finding that muzzles work. But you can’t just rely on a grazing muzzle to fix everything. It is not recommended to use a muzzle 24/7. Maximum recommendations are 10-12 hours, with close monitoring of welfare as well as how it’s working. Rubbing can occur around the face, as well as some issues with dentition, particularly if pastures are short. When the grazing muzzle is not on, make sure to still employ other methods for weight loss. Some of which will be discussed in our future posts. One study did find that when a grazing muzzle was used for 10 hours, then horses were allowed to graze without a muzzle for 14 hours, they still lost weight over a 3-week period. However, for the most effective weight loss, coupling muzzles with other methods such as slow feed hay nets and balanced rations will be the most effective. And of course, making sure your horse gets proper exercise. In order to be able to monitor effectiveness, body condition scoring is the most helpful if you don’t have access to a scale. Follow us for the next part of our series where we will be discussing how to body condition score your horse, and what it can tell you! IYou might be wondering- why do I need a consultation? Or what all do I get when I sign up for a consultation? Well, we're here to answer your questions on anything horse related. For starters, the most basic process that we do is to evaluate your current ration. We look at what your horse needs on a daily basis, and what you are currently feeding them. We then evaluate how their diet is meeting their requirements, and if there are any "holes" or gaps where some nutrients may be deficient, or some might be in excess. We provide you with not only a write-up, but also visual depictions of what your diet looks like compared to your horses' needs. It is important that we have as detailed information as possible, including not only what you are feeding, but the amounts that you are feeding them to your horse. Here's an example of a diet that we evaluated for a recent client. This graph shows how each nutrient is doing at meeting the horses' needs as a percent of requirements. Some nutrients like Magnesium and Calcium were very close to meeting their needs almost exactly. However, Iron (Fe) was excessive, exceeding requirements by about 225%. We were then able to come up with several diet options based on what feedstuffs the client had available to create a diet that better matched the horse's needs.

We also evaluate nutrient ratios, because nutrients interact with one another. Some, like Selenium and Vitamin E, can enhance the action of the other. Others, such as Copper, can interfere with Selenium absorption (we will address some of these in future blog posts). Therefor it is important that they are not only provided in adequate amounts in the diet, but also that they are in appropriate amounts in reference to other nutrients. We are also happy to evaluate all of your forages and their nutrient quality, or if you are interested in comparing supplements, we are happy to do that as well. We can research the supplements that you are interested in, and provide you with a concise write up regarding the research surrounding that product, and how it might work for your horse. Same goes for various feeds or forages, we are happy to do the leg work for you and evaluate which might be best, looking at both effectiveness for your horse as well as economics for you. So contact us today to evaluate how your feeding regimen suits your horse(s)!  First of all, I’m so excited to be part of this new venture with Emily! We hope by offering some insight into our backgrounds, you can get to know us a little better and understand why we’re so passionate about what we do. I’m Cassie Wycoff, and aside from Field & Fodder, I provide livestock, forage (hay/pasture), and equine expertise as an Area Extension Agent and Equine Extension Coordinator for Clemson Cooperative Extension in South Carolina. I moved to Upstate South Carolina about five years ago to accept my current position and love working with Extension. Like Emily, I travel throughout the state speaking and organizing workshops for various topics on animal health, nutrition, and farm and forage management. I also work closely with several local and state livestock and grazing associations and equine councils. I’m originally from a small town outside of Raleigh, NC, where my family owns a horse and hay farm and boarding facility. Without much choice, my family had me on a horse at a very young age; and, although at first I wasn’t the typical horse-crazy little girl, my natural love for animals eventually took over by the time I reached middle school. Aside from my family’s involvement in the local saddle club, I joined our county 4-H horse club, which jumpstarted my interest in showing and training horses for both english and western events. Also through the 4-H Horse Program, I had the opportunity to compete on the state 4-H and NCQHA horse judging teams, traveling to many national and regional contests, which later continued in my collegiate judging career. After high school, I attended North Carolina State University, where I completed my bachelor’s degree in Animal Science. The summer after graduation, I began assisting Dr. Siciliano with his research in attempt to gain more experience and as a resume-builder. Luckily with some slight urging from Dr. Bob Mowrey, North Carolina’s Extension Equine Specialist (now retired) and long-time mentor from the 4-H horse program, I decided to make it official and pursue graduate school. I completed my Master’s under the direction of N.C. State Equine Nutritionists, Drs. Paul Siciliano and Shannon Phillips. It was there that Emily and I met and bonded over many long hours at the research farm and a whole lot of sampling and fence building! My masters research focused on management strategies to reduce the incidence of laminitis and other metabolic disorders in mature pasture-raised horses. We investigated the seasonal and daily fluctuations in the sugar and carbohydrate concentrations of pasture grasses and the implications those fluctuations had on the hindgut health of the grazing horse. What I loved most about my research was the practical application it had for every horse owner. During this time, I realized the huge impact that nutrition has on equine health and performance and how often it’s overlooked. I really enjoy being on the preventative side of equine health management, but I know that today’s horses face many nutritional and management complexities that they weren’t exactly designed for. Together, Emily and I hope we can share our expertise to help limit the risk of many of these nutrition-related diseases and the impact they could have on your horse’s health and performance career. When not at work or planning our upcoming wedding with my fiancé Christopher, I can usually be found at the barn riding. With my 4-H mount happily enjoying the semi-retired life back home in North Carolina, I’ve been fortunate enough to lease and work with some very talented young horses here in SC. My current lease is a triple registered 5-year-old paint/pinto/quarter mare named Livi (short for “Living The Dream”), and together we show on the APHA circuit in South Carolina and regionally. We even had the opportunity to show at our first Pinto World Show last year, where we brought home a reserve buckle and several top five placings! Thanks for your interest in Field & Fodder, LLC, and we look forward to working with you. Feel free to contact us to learn more about how we can help your operation enhance its nutrition management program for both your horses and pastures. Why should you test your hay?

Dr. Emily Glunk Meccage For many livestock and horse owners, testing your hay is not something that is done on a regular basis. And in many cases, most will rely on their animals’ performance to gauge how feeds are meeting their needs. This can work for many people, but what about in the case of a performance horse, or a broodmare, or a horse with metabolic or other health issues? If those horses start to have decreased performance, that can have significant implications on the overall well-being of the horse, including decreased performance in the show ring, problems with gestation and foaling, or prolonged disease incidence. Instead of just adding more grain or supplements to your daily feeding, it is usually more cost-effective and beneficial to first know exactly what your horse is getting from the hay and pasture.

I am Dr. Emily Glunk Meccage, co-owner and consultant at Field and Fodder Consulting, LLC. In addition to working at Field and Fodder, I am also the Extension Forage Specialist and Assistant Professor at Montana State University in Bozeman, MT. Part of that position entails coordinating and conducting research on best forage management practices, from fertilizing and grazing recommendations, to appropriate species for producer needs. I get to travel all over the state and region, organizing and speaking at workshops and field days about forage production and management.

My passion is, and always has been, equine nutrition and management. Growing up, I competed in hunter/ jumpers as well as dressage. I also was a member of the riding team at Penn State University for a few semesters, where I completed my B.S. degree in Animal Bioscience. While there, I was fortunate to start my career in research working on two projects with Dr. Burt Staniar: one evaluating the palatability and digestibility of Teff hay when fed to horses, and another evaluating maternal diet impacts on foal performance through the first 18 months of life. From there I was hooked, and knew I wanted to go to graduate school for equine nutrition. After graduation, I started my M.S. degree at North Carolina State University working with Dr. Paul Siciliano. My thesis research involved evaluating horse dry matter intake rates while at pasture. The results were fascinating; horses changed their intake rates based on how long they were allowed to graze. In short, if horses knew they were only allowed to graze for a short period of time each day, they would speed up how quickly they ate. Dr. Siciliano used results from this research and several other projects to create an equation to estimate intake rate based on hours of turnout, which we use frequently in our ration balancing. For fun, I was also able to compete for two semesters on the NC State Dressage Team, allowing me some much needed time in the saddle in between classes and research. While at NC State, I was also fortunate to start learning more about pasture and forage management, which I found extremely interesting. When searching for an advisor and school for my PhD, that was one of the important factors I considered. I was lucky to find a perfect match at the University of Minnesota, working under Dr. Krishona Martinson, the Equine Extension Specialist, as well as Dr. Craig Sheaffer, Forage Agronomist. My research at U of M evaluated forage utilization by equines, both while grazing and consuming hay. One of my projects evaluated how effective grazing muzzles were at decreasing intakes at pasture, and the other two evaluated the effectiveness of slow-feed hay nets as well as their impact on glucose, insulin, and cortisol response. Since starting at Montana State University in 2014, I have had the opportunity to speak around the region several times regarding forage management specifically for horse owners, among many other topics. I currently have four horses; my 3 year old Dutch Warmblood Django (out of my mare Khenya), a 16 year old Quarter Horse Jimmie, who found a new career as a jumper after a lifetime as a trail horse, my auction pony Penelope that my mother bought out of an auction pen in New Jersey, and my mini donkey Donk, who I will be posting about his weight loss journey in the upcoming months. Along with the horses, my husband Ryan and I have two rescue pups, Milly and Tucker, and two cats, Salty (aka Hell Cat) and Harry, who love to keep us entertained. I am very passionate about horse management and nutrition, as well as hay and pasture management. Together with Cassie, who worked on her M.S. degree with Dr. Siciliano at the same time, we realized our passion and experiences could really help horse owners in optimizing their horse and pasture management. We are both very excited to have the opportunity to work with you, and we look forward to hearing from you soon! |

Archives

July 2018

Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed